3 Insights

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.” — Richard P. Feynman

“On the highest throne in the world, we still sit only on our own bottom.” — Michel de Montaigne

“History is the version of past events that people have decided to agree upon.” — Napoleon Bonaparte

What I Learned this Week

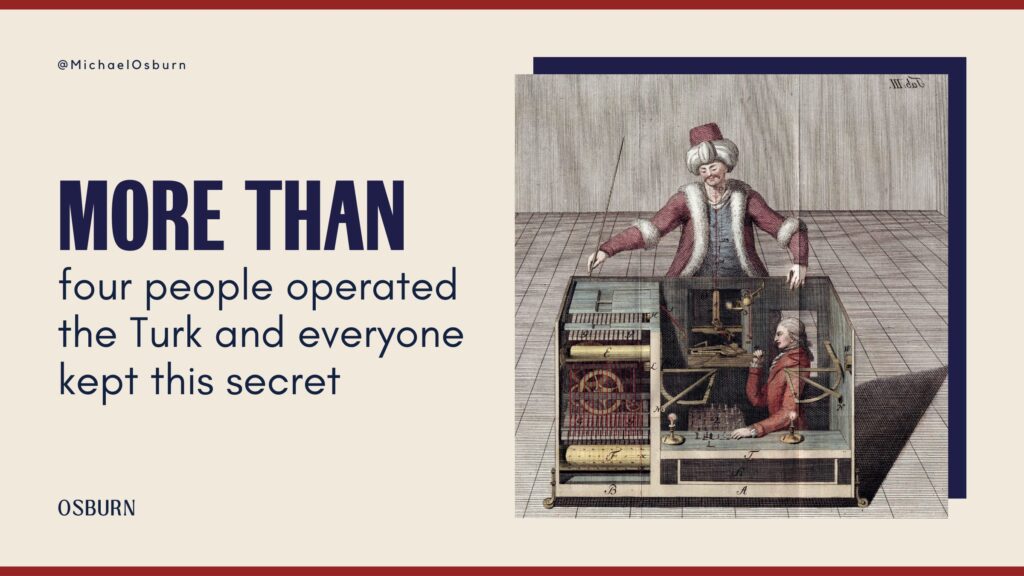

In 1770, inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen unveiled The Mechanical Turk, an automaton capable of playing—and winning—at chess against humans. For 84 years, it amazed European audiences, outsmarting figures like Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin.

Green Canyon (Martin Sanchez)

In other words, more than 250 years ago, someone invented a machine that was better at chess than almost anyone else on the planet! Well, sort of…

There’s a stellar deception tactic beneath this illusion of “mechanical” genius. The Turk’s intricate gears were visible through designed compartments, which misled observers into believing it operated autonomously. In reality, there was a chess master hidden that controlled the game from inside. The chessboard’s thin surface concealed a magnetic system that transmitted moves, allowing the operator to respond. Each piece in the chess set had a small, strong magnet attached to its base; and when they were placed on the board, the pieces would attract another magnet linked to a string under their specific places on the board.

After decades of tours, the Turk was acquired by the Peale Museum in Baltimore, where it continued to mystify visitors. But in 1854, a fire occurred in the museum, and the Mechanical Turk was destroyed. One of history’s greatest magic tricks thus vanished—a machine that never played chess at all, but made the entire world believe it could.

The Illusion of Tyranny

Monarchies, with all of their pros and cons, are fascinating. My bet is that, without a clear understanding of aristocratic values and how monarchies work—democracies can’t be strong.

Let’s talk about the French Revolution and the reign of Queen Marie-Antoinette. In other words, the Reign of Terror and the fall of the French monarchy.

Before the Revolution, there was a growing tension for decades fueled by social inequalities. Under the Ancien Régime, society was divided into three estates: the First Estate (clergy), the Second Estate (nobility), and the Third Estate (commoners). The commoners comprised roughly 98% of the population but had little to no power and were often outvoted by the other two estates. Frustration grew for a long time, and when economic challenges hit, resentment turned to outright fury.

It’s important to consider the figures at its center of that time—King Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette. Their marriage in 1770 was a political alliance between France and Austria. From the beginning, Marie-Antoinette faced hostility from the French public. They saw her as a foreign spy, a feeling that only grew as the financial crises worsened.

The Queen’s spending and lifestyle—while not unusual for royalty—became symbols of excess. The infamous phrase attributed to her, “Let them eat cake,” was likely fabricated, but it fits neatly into the narrative of an out-of-touch monarch not caring about her people. The truth was more nuanced and complicated. In many ways, Marie-Antoinette was stronger than Louis, encouraging him to resist Revolutionary demands; but his indecisiveness doomed their efforts.

When the Bastille fell on July 14, 1789, it marked the beginning of an open rebellion. Marie-Antoinette urged Louis to seek refuge with his army, but he hesitated (again), choosing instead to remain in Versailles—a fatal mistake.

The following months saw the erosion of royal authority. In October of the same year, an angry mob, driven by both rumors and hunger, forced the royal family to relocate to Paris.

What happened next is a lesson in how revolutions often devour themselves. The same people who had initially demanded reform turned into a mob that demanded blood. The image of the king and queen as extravagant and indifferent rulers was, in many ways, a tool used to justify their execution. The vilification of Marie-Antoinette, in particular, was extreme—she was portrayed as a greedy, manipulative foreigner, a corrupting force who had drained the nation’s wealth. It was easier to direct the people’s anger at a single figure than to confront the systemic issues that had plagued France for not years but centuries.

The dangers of mob rule were evident. The Revolution, originally about liberty and justice, spiraled into the Reign of Terror, where accusations and paranoia replaced the rule of law. Those who had fought for democracy found themselves on the scaffold. The lesson? When people allow rage and fear to dictate justice, they often end up destroying exactly what they fought to build.

From history, we should learn that no movement—no matter how righteous in its origins—can survive without reason, restraint, and awareness, especially of human fallibility. Demonizing individuals instead of addressing systemic issues rarely leads to real solutions.

The French Revolution reminds us that real change must be built on principles, not just passion. The chaos of unchecked anger can easily become as oppressive as the regime it seeks to overthrow.

Reflections

Have you ever found yourself influenced by the emotions of a group rather than your own judgment? How do you manage your own fear when everyone around you is fearful?

The Real Con 115