3 Insights

“You will never understand bureaucracies until you understand that for bureaucrats procedure is everything and outcomes are nothing.” — Thomas Sowell

“A system is more than the sum of its parts, and more than a mere aggregation of relationships between parts.” — Gregory Bateson

“The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design. We cannot, after all, know the far-reaching consequences of any action in a world that is not just a collection of independent atoms but a complex web of interdependencies.” — Friedrich Hayek

What I Learned this Week

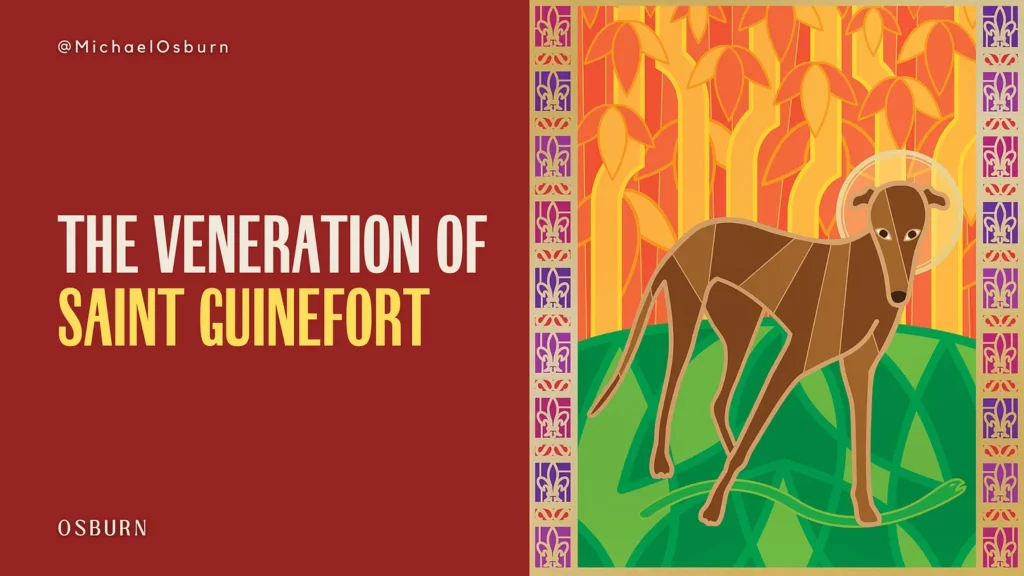

Here’s a legend I came across a few years ago—the story of the first animal ever to be considered a saint. His name was Saint Guinefort, a greyhound, and his tale comes from the early to mid-1200s in medieval France, near Lyon.

One day, a knight went hunting, leaving his infant son in the care of his dog, Guinefort. Upon his return, he found the nursery in a huge mess—the cradle overturned, the child missing, and Guinefort with blood on his jaws.

Fearing the worst, the knight assumed that Guinefort had killed his son and, in his panic and anger, immediately killed the dog. But then, he heard the sound of a baby crying. Rushing to the cradle, he found his son, unharmed and safe, with the body of a snake nearby—clearly killed by the dog in an effort to protect the child.

Guinefort had killed the snake and saved the child. The family dropped the dog down a well, covered it with stones, planted trees around it, and set up a shrine for Guinefort. Upon learning of the dog’s deeds, the locals venerated the dog as a saint and visited his shrine of trees when they were in need, especially mothers with sick children.

Even though the Catholic Church repeatedly condemned the veneration of Saint Guinefort, the belief in his miraculous deeds endured for centuries, as people continued to honor the loyal greyhound who gave his life to protect a child.

This event proves how critical courage and skin in the game are to inspire faith; recall that Jesus Christ did the same—he was willing to endure suffering and sacrifice his own life for the greater good.

The Cobra Effect

Since we’re talking about snakes…

A famous anecdote describes a scheme that the British Raj implemented in India to control the population of venomous cobras plaguing the citizens of Delhi.

The government offered a bounty for every dead cobra brought to the administration; at first, the policy looked promising. Brave snake catchers claimed their rewards and fewer cobras were spotted around the city. But then—instead of decreasing—the number of dead cobras brought in for payment began to rise steadily each month. It wasn’t long before the authorities realized what was happening: the locals had started breeding cobras to kill them and claim the bounty. The program was immediately ended, and the cobras were released back into the wild. As a result, the cobra population surged, leaving the city with more snakes than ever before.

The Cobra Effect also is known as the “perverse incentive.” This is a lesson about second-order effects. Whenever we take action, we might get the result we want, but unexpected consequences might happen too. These can also be called policy surprises.

To avoid these surprises, we need to better understand how cause and effect work in complex systems. The world doesn’t work in simple, straight-line patterns—many factors influence each other in loops. There is nuance to everything in life!

Mark Twain, in his autobiography, describes a similar experience his wife, Olivia Langdon Clemens, had. In Hartford, they faced a fly infestation.

“Mrs. Clemens conceived the idea of paying George a bounty on all the flies he might kill. The children saw an opportunity here for the acquisition of sudden wealth. Any Government could have told her that the best way to increase wolves in America, rabbits in Australia, and snakes in India, is to pay a bounty on their scalps. Then every patriot goes to raising them.”

Another example of this effect is when Wells Fargo, one of the largest banks in the US, found itself at the center of a scandal when employees, pressured to meet aggressive sales targets, began opening fake accounts to earn bonuses and avoid losing their jobs. Millions of unauthorized accounts were created, and the scheme continued for years before being uncovered. When it came to light, Wells Fargo faced massive fines, lawsuits, and a loss of trust.

The Cobra Effect is a reminder that, when rewards are tied to specific, measurable outcomes without considering the broader consequences, people will find ways to manipulate the system—often worsening the original problem.

Reflections

What is my first instinct when I see something isn’t working—do I attack the symptom or do I look for the root cause?

The Real Con 117