3 Insights

“The heaviest penalty for declining to rule is to be ruled by someone inferior to yourself.” — Plato

“Nearly all men can stand adversity, but if you want to test a man’s character, give him power.” — Abraham Lincoln

“People will do anything, no matter how absurd, to avoid facing their own souls.” — Carl Jung

What I Learned this Week

This week, I wanted to share a story from ancient Athens—a practice that seems radical by modern standards, but one that reveals much about the way citizens viewed democracy: ostracism.

In ancient Athens, ostracism was a peculiar yet democratic process. Every year, the citizens would gather to vote on whether a person should be expelled from the city for a decade. The person in question could be anyone—from a powerful leader or politician to someone with personal rivals. The purpose of the vote was to safeguard the health of Athenian democracy. Ostracism was used as a way to remove those perceived to be gaining too much power or influence, or simply those who were disliked or feared.

Ostracism wasn’t about punishing criminals; it was about maintaining balance and ensuring that no individual could dominate the political landscape. You could say it was an early attempt at political accountability, though, in practice, it often felt like a tool for revenge.

We no longer banish politicians from their roles for a decade, but we do have ways to remove them from office, such as through elections or impeachment. But would we, as voters, ever go so far as to force someone into political exile, even if we didn’t have solid evidence of criminal wrongdoing? Could we, in good faith, ostracize someone based on fear or suspicion?

The Philosopher King and the Reckless Son

When Marcus Aurelius, one of Rome’s greatest emperors & philosophers died in 180 AD, his son Commodus took over. Marcus had spent his life trying to rule with wisdom, self-discipline, and humility. He tried hard to raise Commodus with those same values. Marcus tried to surround Commodus with the best tutors he could find, hoping to mold a future leader who would care for Rome as much as he did.

Unfortunately, the son had a whole other interest. Instead of studying philosophy or preparing to govern wisely as his father did, he did more trivial things like gladiator fights and public games. Where Marcus wrote about duty and restraint in Meditations, Commodus sought glory and entertainment—not for Rome’s benefit, but for his own amusement.

Cassius Dio, a Roman historian who lived through these times, described Commodus’s reign as the moment Rome fell “from a kingdom of gold to one of iron and rust.” That’s how sharp the decline was.

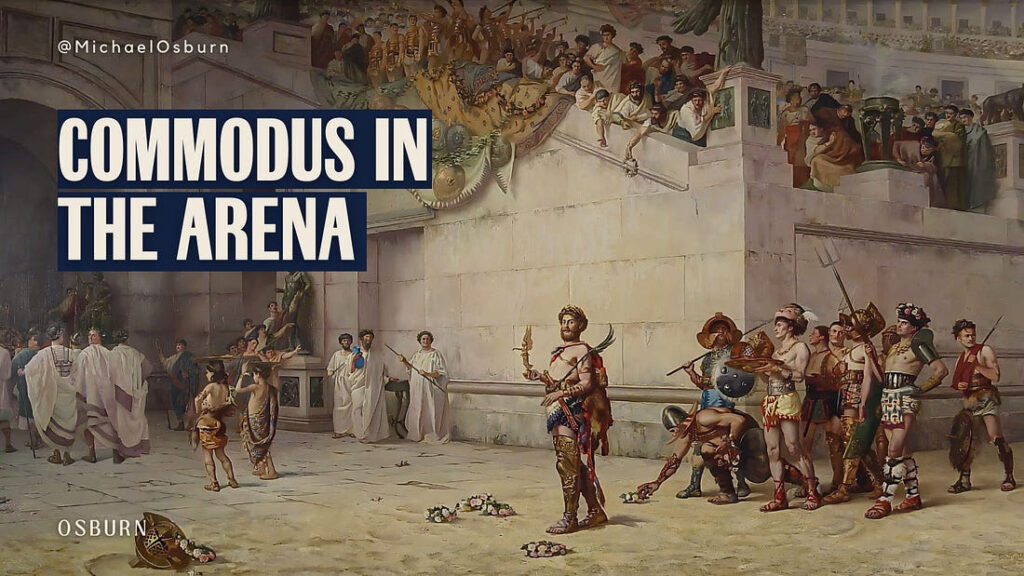

To put this in perspective, gladiators in Rome were typically slaves, criminals, or prisoners of war—people forced to fight for the entertainment of the mob. An emperor, the symbolic “father of the nation,” was supposed to be wise and above such spectacles. But Commodus didn’t care about the rules. He fought as a gladiator, parading his strength. Commodus was also known for fighting exotic animals in the arena, often to the horror and disgust of the Roman populace. According to Cassius Dio, Commodus once killed 100 lions in a single day.

In doing so, Commodus blurred a crucial line—between ruler and entertainer. By turning the imperial office into a personal stage, he degraded his role as the emperor. What was once a sacred duty to serve Rome became another way for Commodus to show off and feel powerful.

Marcus Aurelius lived by Stoic values, always aware of how fleeting power was, always seeking to lead with humility for the good of the empire. He saw ruling as a responsibility, not a prize.

Reflections

What does power mean to you? What is the example that you set at home or work?

The Real Con 119